Professor Frank Vigneron, Law yuk-mui and Yim Sui-fong in conversation with Nguyễn Trinh Thi and Ocean Leung Yu-Tung

Date: 11 January, 2017

Proofreading: Professor Frank Vigneron, Law Yuk-mui, Yim Sui-fong

Editing: Law Yuk-mui, Yim Sui-fong

Exchange and Gap

Yim Sui Fong: Thi (Nguyễn Trinh Thi), I knew that you joined the "Food and Farming Festival" at Mapopo Farm, curated the screening project "Hanoi DocFest in Hong Kong" at HKICC Lee Shau Kee School of Creativity and also participated in the protest on 2017 January 1. How do you describe your experience in researching Hong Kong movies during the residency, in particular the interview with Paul Au Tak-Shing, a refugee who escaped the war to Hong Kong from Saigon,Vietnam in 1975?

Nguyễn Trinh Thi: For me, I’m a slow person, so I need to have a lot of time for digestion. Although I might have some vague questions that might be related to my previous experience or interests for this residency programme, I would live and just stay open to chances. I try to have this element of chance in my work. I would say that it’s a kind of combination of control and chance. So any of these experiences that I happen to have, they occurred quite out of expectation. I didn’t really have any idea from the beginning that I would join all these things or protest. And I think all of these fragments, like jigsaw puzzle can fall into a big picture. But I don’t want to rush to sum up the whole picture yet. I tend to have a little bit of distance with the present. So I prefer to use or look back at the footage that is already a bit old. I think maybe in that way, the research of the films from the 80s to early 90s can be interesting for me.

Yim Sui Fong: And you must be happy to meet Paul Au Tak-shing, because he was active in the 1970s

Nguyễn Trinh Thi: Exactly, I interviewed him quite early during this residency, like almost immediately after I arrived. So it was very interesting for me to have an entry into this big picture through a personal story. And from his story, there were some important points that popped up and needed to be answered, or to realise the connection, and then I started to read more about other refugee situations in the time of the Vietnam war, and then later how Hong Kong movies represented the boat-people situation.

Thi interviewed Paul Au Tak-Shing, a refugee who escaped the war to Hong Kong from Saigon,Vietnam in 1975

Yim Sui Fong: Ocean (Leung Yu-tung) , how would you describe your experience in this project?

Ocean Leung Yu-Tung: It was quite experimental because this is my second artist-in-residence, and both of them are in Hong Kong. It feels like falling into a time machine, because at the same time I was in a documentary film project with my friend Freddie Chan Ho-lun. We had started to study the stories about the New Territories, about how villagers and farmers protest and live there. It was not our intention to investigate from the perspective of their history. Meanwhile, this programme has exposed more to me how to connect the dots. In fact, I seldom travel to Hong Kong Island, because most of my activities happen in the New Territories. But when I'm living on Hong Kong Island at the residence, I discover more of the colonial history of Hong Kong. For example recently there is a group called “Watershed Hong Kong” who research the war called “Battle of Hong Kong” and investigate how the soldiers of Great Britain and Canada fought for Hong Kong, and it led me to think about the war, the violence, and the connection to the past. In the public talk, I mentioned the Six Days War in Hong Kong, comparing those poor farmers and villagers to those World War II soldiers with full gear; they looked really different. When we compare the act of defense, in my point of view, the villagers were just protecting their own property, but those British soldiers were defending the power’s properties, not necessarily fighting for justice. They were just agents sent by the colony. This has brought me a more complicated point of view on Hong Kong history.

When I was in the cemetery at Happy Valley, I saw that many people who once lived in Hong Kong died from various military actions around the Asian region. It showed the consequence of British colonialism on the lives of individuals. The casualty made me associate colonialism with the violence behind politics.

Law Yuk-mui: As this is an exchange program, would you both share the conversation you had between the two of you? Thi curated a screening in the Creative School that Ocean attended. Thi also visited Ocean’s studio in Fo Tan, and you both led the workshop and worked together. Can you tell us more about this?

Ocean Leung Yu-Tung: It opened up my thinking. Because I am a party goer, I always go to openings. However, from the collaboration with Thi on the basics of video production, I saw her concentration, in particular about her own artistic concern and video making education. I have learnt a lot about local identity and activism from the dialogue with her. She inspired me to be more focused on what I could do with art. This helps me think about investigating the possibilities of the medium itself and how it is essential for generating social impact. Although we are working on different social contexts, she is inspirational.

When Thi visited my studio, she asked about my friend’s music creation, and Hong Kong movie stars and we talked about that all night while we were celebrating New Year’s Eve. We watched youtube channels like CapTV, remember?

Nguyễn Trinh Thi: The fake one where they use the classics and …

Ocean Leung Yu-Tung: There’s a channel called CapTV. And they use scenes from gangster movies to joke about the Hong Kong elections, and they re-do voice over with found footages. This exchange reminds me that I need some kind of environment in art to exchange idea; and actually the environment is already around me. And I think it’s good to have this experience at this moment because my artist career just started a year ago. This program helps me stay focus and calm to organize my daily schedule.

Frank Vigneron: That means you like the focus and the seriousness because you have been lacking that for a long time.

Ocean Leung Yu-Tung: Details and focus. From Thi I found and learn about attitude and patience. Every time we talked, we stuck to the core of the discussion/ important thoughts. I also enjoyed the residency as it has provided a space for contemplating, observing, reading with or without purpose rather than producing “new” works. It encouraged well-thought planning about the possibilities of the research direction - these are important.

History & Moving images practice

Yim Sui-fong: Let’s talk about the practices. Thi, why is your creation concerned about “investigating the role of memory in the necessary unveiling of hidden, displaced or misinterpreted histories”? Your practice involves making use of found footage, taking up the form of documentary, and it is now also concerned with the topic of landscape. Can you share with us this development?

Nguyễn Trinh Thi: Actually the quotation you mentioned is not mine, but from others reviewing my work. It’s not a bad description. When I look back at my works, I think a lot of them attempt to be related to memory and our relationship to the past or history. Because one of the issues for artists that we always deal with is the question of what is our position in this life, in this reality, in this history. We would look at what we have learnt before, and what history told us. [We look at] the books and all kinds of situation that help us come up with our understanding, but we would find out that there are a lot of lies in that information, especially like in Vietnam, when we grew up. That is a one-party country and the history is rewritten by the official, the party, everything like that. So we didn’t really receive any true information at all, like either through education or media until today. All the history was fake and distorted. So how can we justify our understanding after we receive all that fake information? I think it becomes a beginner’s step even just for me to unwind everything and in the process I would have many questions: what is history, who is authorized to write it, what can be a legitimate source of history or information. So it's not simple. It's complicated, and you would come up with your own kind of thinking of what made up history. Everyone has the kind of value in contributing to what is history, even the very unimportant sources or the kind of stories that is not directly related to very important events as we usually perceive them. That’s why I really like this version of history, like a personal story, like the one from Paul. Actually from his story or my conversation with him, it’s interesting because many parts of his commentary are opposed to what we would understand to be typical events. For example, normally you would think of a war with victims, suffering and unhappiness. But for him the war time was the best time of his teenage life, and he just couldn’t stop talking about how happy he was (e.g. the American cultural influence). That was relating to personal memories and I found it very interesting. It is a complex system that we have to deal with and we have to decide how we would want to relate to history and what we allow to enter as history.

Frank Vigneron: This sort of goes back to the beginning of this conversation when you were saying that you are always in a position of expecting things to happen, that you take it slow and so on. But actually to me, your approach strikes me as very much based on research, so again it seems to me more proactive than the way you presented it. I do realize that Paul’s interview, for instance, was accidental. Without Andrew Guthrie’s books at Art and Culture Outreach (ACO), we would have never found him. At the same time you come to that interview with already a huge amount of research on the topic of migration, on the Vietnam War and so on. You see this as very casual, and I see this as research-based.

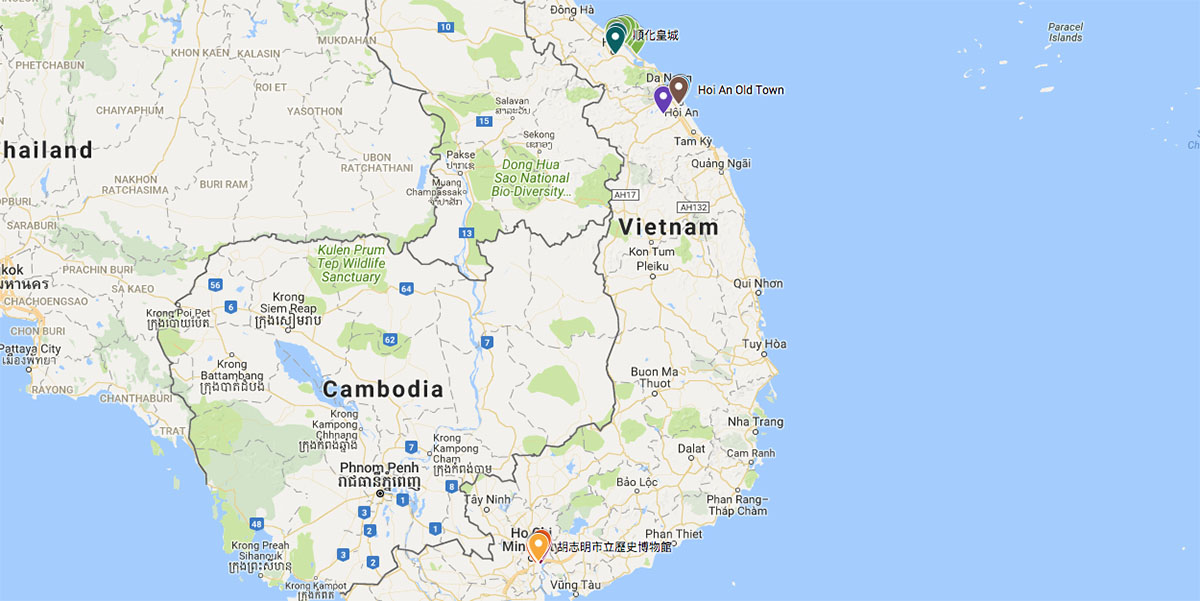

Nguyễn Trinh Thi: I think that probably my approach has two layers. Maybe one layer is based on some foundation and previous knowledge and research, and then also some formulation of potential questions to go forward. But on the other layer, it’s based on chance. So in that way I think my approach is to keep it open for new discovery, and although I formulated certain questions, I get informed by new encounters, and then I would look at these formulated questions again. So in this case I wouldn’t say that it was specific, but it was a kind of an extension of my previous work Vietnam the Movie. It was related to the relationship between Vietnam and the world, and in particular during the time of the Vietnam War. And I became more curious about an Asian perspective because Vietnam the Movie was seen through the eyes of mostly the West, with the exception of a few movies from Asia. It looks like we still have the legacy of the Cold War when all these Asian countries were divided and served different sides. So I came to Hong Kong with these questions. Maybe this would be a good chance for me to open it up a little bit to the Asian perspective of the same question. And then by chance, Hong Kong was an important country of these divides in the Cold War and also has some relation with Vietnam, especially the post-war Vietnam, so it serves as a really good place to extend this research. So my question when I first came to Hong Kong was a bit broader than now: a potential Asian perspective of different Asian countries. But during the residency, I think it became a bit more focused on Hong Kong when I look at the films and started to map the relationship between Vietnam and Hong Kong since the war and after.

Hong Kong director Ann Hui has three pieces of works about Vietnam, including the From Vietnam(1978) in Below the Lion Rock TV programme series, The Story of Woo Viet (1981) and Boat People (1982), common known as Vietnam Trilogy. (images from internet)

Another thing that emerged from the research was the Chinese and Hong Kong identity which become more complicated. It’s not just the bilateral relationship between Vietnam and Hong Kong anymore, but it’s expanding. Because, as far as the Vietnamese refugees who came from Saigon to Hong Kong were concerned, actually a lot of them were Chinese. So Vietnam is like a transit stop where they stayed for a while. They may not totally have had a Vietnamese identity but tended to lean towards being Chinese. So it’s a part of a bigger network, like what it means to be Chinese is sort of circulating through all these parts. And then what also happens now to the Hong Kong identity as well. Hong Kong was handed over to China in 1997. So I feel like the picture is getting expanded and I tried to stitch all these pieces in which Vietnam was one part, but the map is getting bigger.

Vietnam the Movie (2016) , Single channel video, 47 min, color and B&W, sound

Law Yuk-mui: Ocean, you used “reportage” to describe the two documentary films you produced. How do you treat the topic of “history” and “video as a medium”?

Ocean Leung Yu-tung: My production team and I found that we don’t want to repeat ourselves by just doing interviews, collecting oral history from others. Because we want to move on to push the boundary on form and experience, to experiment on documentary film to see how far we can go. When my friend saw our previous documentary films, The Way of Paddy and Open Road After Harvest, and asked what is our intention to set such a topic to develop, we found that the initial idea was to make a documentary film to participate in the protest, rather than bearing a question to investigate. Now, as documentary film makers we are trying to find more challenges from modern perspectives. It is also the reaction reflected by the recent years’ so-called Hong Kong independent films practice and movement, because most of us are making things by reacting to the present, but we never have enough time to do research or to react. Freddie and I found this problematic. And after two films we couldn’t do this anymore, because social media and the internet are doing the same thing. They are responding even faster with insight by writers but not film makers. So the medium may have some constraints if we want to do a full length feature documentary.

The Way of Paddy (2013), Hong Kong, Color , 128 min, Cantonese, Chinese and English Subtitled. Director: Fredie Chan Ho-Lun, Producer: Ocean Leung Yu-tung.

Frank Vigneron: The way we look at documentary film making is usually by associating it with the idea of being objective, the reality of things and so on. This also makes me think about how many artists conceive socially-engaged practices, the way it is supposed to deal with real social issues. When looking at socially-engaged art practices however, some people react by wondering why on earth artists would do this when social workers might be doing a much more concrete job. I think similar reactions might come up when we talk about documentary film makers: what are they doing differently from the people and who react immediately to situations by using simple tools and social media and do not see themselves as artists.

Asia & Local

Frank Vigneron: Thi, what do you think of the now widely accepted notion of ‘Southeast Asia’ (there are even books with titles like A History of Southeast Asia, where China is only mentioned as a source of emigration in the production of ‘Euro-Chinese cities’)? Many scholars are questioning this notion as too limiting and unlikely to allow an understanding of these places as part of a global network with a long historical reality (the way Singapore has positioned itself as a ‘center’ of Southeast Asia for instance could be seen as a new form of Imperialism). As a Vietnamese artist, did you have to face restrictions or difficulties as a ‘southeastern Asian’? Or has it been beneficial on the whole?

Nguyễn Trinh Thi: I think this question is so difficult; I can only tell you my personal experience and background to see how it relates to Asia. Like growing up in Vietnam, especially northern Vietnam, it’s a very unique experience. Because it is in a part of a very strange network Vietnam was on this side of the Cold War for a very long time as a communist country. Meanwhile Southeast Asia was so divided. When I grew up, I didn’t have any concept of being a part of Southeast Asia. I also think that even now, when I started to travel to Southeast Asia or have friends who are from there, I still don’t quite relate myself to their culture.

Because we were much more influenced by Chinese culture, especially North Vietnam. On the other hand, I think most of the Southeast Asian culture is more influenced by Hinduism. It has a flavor of Indianisation or Hindu culture. But centuries ago, North Vietnam was one country, and then Central and South Vietnam are like other kingdoms, for instance the Champa kingdom, and they are much more Southeast Asian. Like in my film, Letters from Panduranga, it is about Champa. And they were very much part of a Hindu-influenced culture. Because of the communist government, our culture and our kind of social system were organized by being much more associated with the soviet block or the eastern-European block. So that is another kind of administrative influence. So, actually, if I talk to artists from eastern-European countries, I would share more experience with them than with artists from Southeast Asia. Now people call me an artist from Southeast Asia, but actually I don’t really feel that way. So we have a very weird kind of combination of influences. And then I left Vietnam to study and work in the States for ten years, I also missed a big chunk of developments in Vietnam between 1998 to 2007, which was quite an important time of Vietnam’s development. I left right after Vietnam opened up to the world and became sort of capitalist. And of course because of the colonial past, the culture of Vietnam was also influenced by the French. And now we are living in a globalized world. So now when we talk about any kind of pure concept of Asia or something, I don’t know what it is anymore. It’s very difficult. This interesting or weird mix also makes me feel curious to try to sort things out through my work. So for each project, for example, Vietnam the Movie, I would have to deal with how the world, or the West look at Vietnam from different sides, or how Asian countries look at Vietnam, or what was decided by the Cold War. The other project I worked on touches on the issue relating to the Cham and its relation within Vietnam. For instance, the Vietnamese as a majority and the Cham as the indigenous people in their land, but now they are a minority being marginalized. So there was this kind of complex system of relationships that I just try to deal with, or try to understand through different projects.

Letters from Panduranga (2015), single-channel video, color and b&w, sound, 35mins, in Vietnamese with English subtitles. Photo Courtesy of the artist Nguyễn Trinh Thi

Yim Sui-fong: Ocean, you have mentioned that the constraint of Hong Kong art is too “localized”. Why do you have such thoughts?

Ocean Leung Yu-tung: Hong Kong culture itself is not solid and it changes so fast. In fact, there are a lot of neglected traditional parts of Hong Kong. When I make documentary films, compared with my art creation, I think there is a very big gap. And the gap is caused by the neglect of a lot of things that have happened and might have been important. For example, the history and city development in the northern part of Hong Kong. Being too localized means too centered on one’s own living style, without exploring or understanding more what we call Hong Kong is or was about.

In the 90s, we always used Hong Kong movies, pop culture, and the growth of the economy to talk about the Hong Kong identity. When I did the documentary film on farmers, we realized that this identity just represented the urban cultures and the so-called phenomenon of globalization. When we focus on the metropolitan lifestyle, those people leading a different lifestyle would be marginalized, like new immigrants, villagers, a lot of things…maybe the awareness of being localized is based on my concern for these marginalized groups.