Law yuk-mui and Yim Sui-fong in conversation with Shitamichi Motoyuki and Tang Kwok-hin

Date:6 June, 2017 Japanese

Translator: Yoki Lee English

Translation: Evelyn Char

Editing: Law Yuk-mui, Yim Sui-fong

Began with a walk

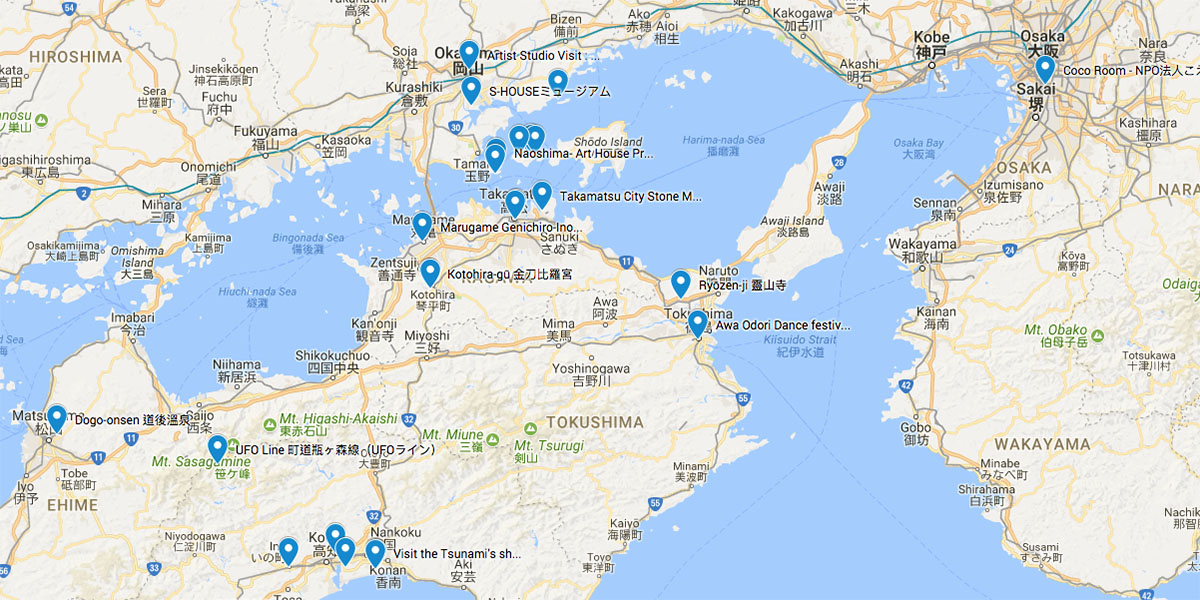

Law Yuk-mui: For the Asia Seed project, Michi (Shitamichi Motoyuki) came to Hong Kong for a residency in March and in May 2017. During this time he wandered around in order to get a feeling of the city space of Hong Kong with his own feet. Later on, Hin (Tang Kwok Hin) brought Michi to the walled villages of the Tang clan in Kam Tin and Ping Shan.

Shitamichi Motoyuki: I think getting to know a place through walking is very important, because only when one walks on foot can one see the size of the road, and the breadth of the country’s territory. Before the workshop began, I had two weeks to walk around most parts of Hong Kong, and then to think about how to conduct the workshop - this has been a great help to me. The things that I saw on the streets became the starting point of my ideas regarding the Asia Seed project. At that time I felt I was able to gauge the contact point of the project: because the theme of the workshop was “everyday object”, I saw how objects were transformed from an everyday context into art. At that moment I felt that the origin was predestined to be here.

Visiting walled villages of the Tang clan in Ping Shan

Observation, discovery, record and naming

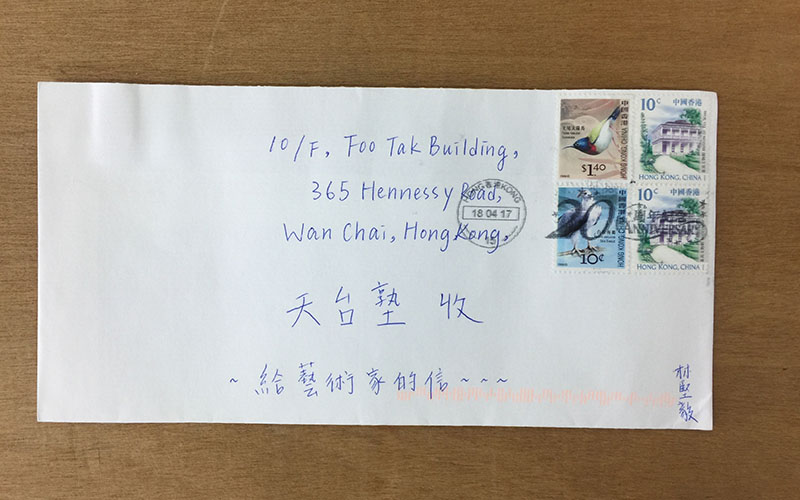

Shitamichi Motoyuki: At a later meeting at Hin’s place, we decided to have some exchanges with the students using letters. Hin felt that this way he could have more time to think about what to do. Through exchanging letters, I could gradually understand what was in the students’ minds, and also get a sense of their individual levels. And I thought to read the letters on Hin’s side could serve as references for my own workshop or works. I had actually been thinking about using

mitate (Japanese which means 'naming' ) as the direction of the workshop from an early stage. At around that time Hin’s daughter was born, and I was told the story of how she was named. I felt that it was an interesting point in time to do this, so in the end I decided to use ‘naming’ as the axis of the workshop. I felt that the name of Hin’s daughter was like one of his works. I also noticed many interesting street names in Hong Kong, for example Hollywood Road and Robinson Road are named by the British. There were some street names invented by Japanese people, for example the Chinese name of Castle Peak Road (青山公路), is actually refer to Japanese medical scientist and doctor Aoyama Tanemichi (青山 胤通) , and some other like Queen's Road and Electric Road were names literally translated from English to Chinese.

I found all these very fascinating, so I decided to design the workshop around ‘naming’, but I don’t want to do it in a heavy way and instead envision it as something more relaxed. Although I’ve decided on naming phenomena in everyday life as the general method, I couldn't come up with a suitable form, until Hin suggested using instagram to conduct this workshop. At that point I thought, actually hashtag was a really suitable tool. After we finished the workshop, I noticed that some students continued to upload photographs to instagram and carried on the naming exercise, from there I saw that they were making progress bit by bit, whether it was the quality of the photographs or the ideas of naming.

Letter by student written in response to a letter from the artists.

In the workshop, one of the best things about the students’ work was that they were able to capture the poetry and beauty of objects. For example, in the past many people would analogise women to flowers, and in this workshop students use snow as a metaphor of the loose cotton of cotton trees. This is a poetic and artistic transformation. Although I explained at the beginning that I hoped the hashtags could be used widely and become a trend, I understood that it was more difficult to achieve this. However, the students did start to use the hashtags of other classmates in the workshop, and I think we are already half way there.

Students taking photo of the special phenomena on street.

Border Research, interview with the local students

Law Yuk-mui: You went to three different secondary schools to do the workshop “14 years old & the world & borders”. When we interviewed you for the “

Who Interviews Whom” column in Sunday Mingpao, we learnt about the rough idea of this workshop. However you see it as the research part of Asia Seed. Why is that?

Shitamichi Motoyuki: I think if one only walks around a city as an observer, he doesn’t really get any exchanges with the place. In order to know a city one must do more than that. Aside from observing, the second thing one can do is to taste local food. The third thing is to try and converse with the locals. Therefore the workshops in the schools came to be conducted as some form of interview. Every time I asked the students if they had any questions for me before we finished, and I would always answer honestly. It was a very special experience, because it was impossible to communicate with them directly and I tried to understand what they were really thinking. For me it was a very important process of getting to know Hong Kong as a place.

“14 years old & the world & borders” workshop in P.H.C. Wing Kwong College.

Law Yuk-mui: After completing the workshop and seeing the textual descriptions about the borders of everyday life by Hong Kong students, what were your thoughts?

Shitamichi Motoyuki: In the workshop I couldn’t understand directly what the students were writing. Instead I had to rely on the reactions of at least three people - Hiko the translator, Mui (Law Yuk Mui) and Sui Fong (Yim Sui Fong) - in order to gauge the meaning and feel of the writing. This was an interesting experience for me, it was as if I was watching from a distance and trying hard to understand from afar what the results were like.

Interestingly, Hiko, Yoki (translator and assistant in the project) and I went to eat before the workshop started, where I explained to Hiko about the contents and goals of the workshop and also my own thoughts. In response, Hiko told me that Hong Kong students probably don’t really have dreams or goals. As they are mostly very ‘dry’, we might not be able to get much out of them. But when he saw that the students all had different ideas and dreams later on, he found the discrepancy between his expectation and his actual experience very interesting. I can’t really single out a piece of writing that inspired particularly interesting ideas or feelings in me, and in fact seeing how the students wrote was not the most thought-provoking part for me. It was rather more interesting for me to see how other people looked at the students. While the writings express many remarkable Hong Kong-style ideas of the students, it was not what I want to see most from the workshop. If possible, I would really like to interview those who read these writings, and find out how they feel about them. I absorbed the most experiences not from the writings of the students, but rather from being inside the school in the process, where I saw the everyday life of the students and the conversations between themselves. That was the more important part for me.

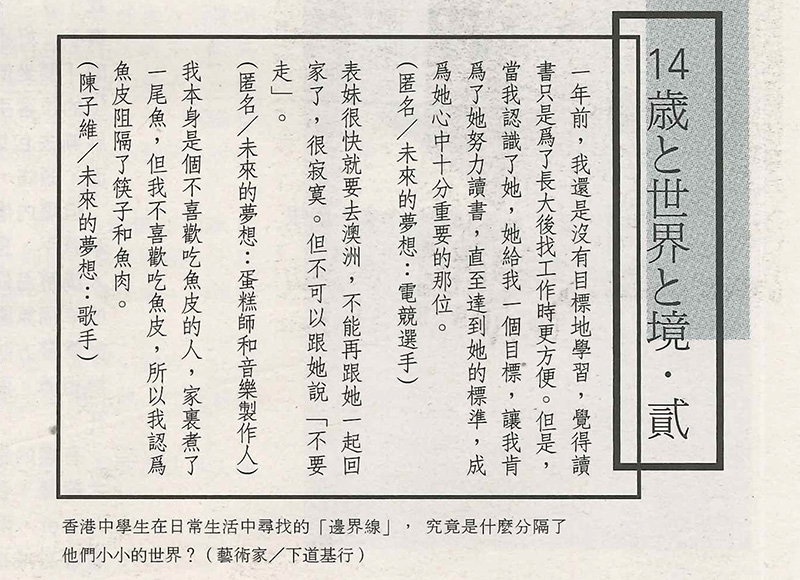

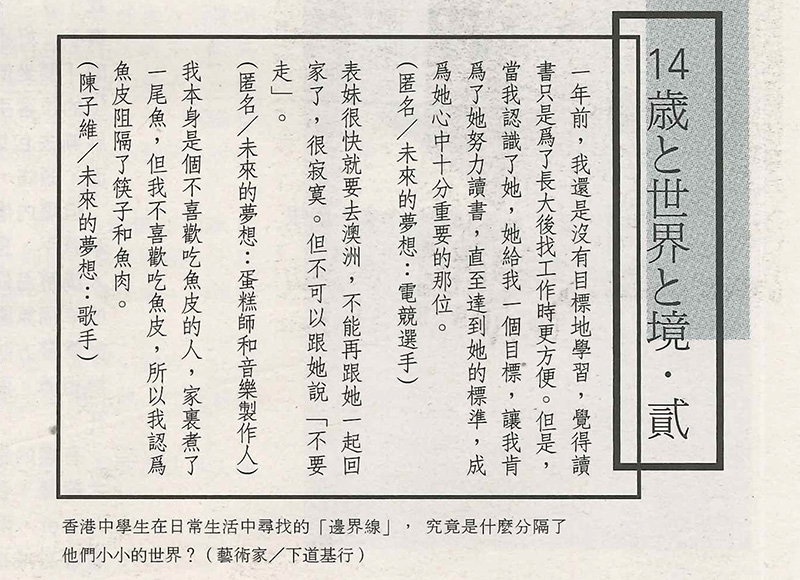

“14 years old & the world & borders” serially publish on Ming Pao's Sunday supplement.

Collect the feeling

Yim Sui-fong: As for Hin, you suggested letter writing as a warm up exercise before the workshop, and your first letter asked the students to share the deepest emotion from their recent life, whether it was happiness, anger, sadness or anxiety…

Tang Kwok-hin: There are always reasons behind artmaking, but is it possible for certain things without reasons to seep through? The issue I raised in the workshop was to reconsider emotions, because feelings can arise without any reasons. For example you might throw things around when you are angry, venting your emotions with no reasons. In the second letter, I asked them to interact with an object using a body part in order to produce a dramatic or aesthetic result, and take a photograph of it. For me the two letters are related to each other. Would it be more intuitive if we can start from an emotion and bring out a feeling? This is also what I’m trying to do, and that’s why I brought the question to the students.

After the first workshop, I felt that more than half the students were confused, but actually I wanted them to feel that way. Confusion can stem from ignorance about a certain topic, or a lack of reflection about it, or a sense of unfamiliarity. In the two-day workshop, we had a picnic and I talked ambiguously. The students behaved well and listened. In the process, it felt like they had no idea what they were listening to. Some students were listening intently, while others were probably trying to ruminate as they didn’t understand. Then, I asked them to start collecting things. I attempted to follow one or two teams, though I lost track of them after a while. Later, I bumped into some other teams. I didn’t see any idle moment when they worked. Rather, some teams had collected some objects that weren’t easy to carry. At the end when we were debriefing… Actually the most important part that day was the sound recording. At the time of packing, or after hearing me speak, or visiting a stranger, the students had already experienced everything and were holding an emotion devoid of contents - what have been accumulated when they spoke into the recorder? Sometimes, creation is about how many inner qualities you have, how much experience you have to process and open up your work. “Accumulation” to me is breaking away from daily matters, storing a special day’s experience into a container of your overall value system that you can open anytime. I hope my students are patient enough to witness their own life anew. When I listened to their recording, I felt that they had entered a certain state.

(Left) Workshop Day 3 at Yuen Long Park. (Right) After collecting the objects, student shared the table in a fast-food store with a stranger and made a sound record of his story.

At the start of the second day, I introduced different approaches of artists who work with “everyday objects”. I felt that these contents were very suitable for them. I also clarified a few things while preparing and I really enjoyed the process. After I finished the introduction, they started doing mixed media exercises according to the topic, with the experience they gained from the workshop. I was actually quite surprised. When I watched them doing it, I didn’t really know how to discuss each work, but in the end, while speaking to the students, I once again found that distinctive feeling of situating in between reason and non-reason in art. This was a great outcome for me, and I hope that the students also got some interesting experiences out of it.

Workshop Day 4 at Tang Kwok-hin’ studio.

Law Yuk-mui: Some students reported that this feeling between reason and non-reason gave them a sense of freedom. This is probably the non-knowledge part of art education.

Art Education between Hong Kong and Japan

Tang Kwok-hin: I started having a lot more imagination about education because my daughter was born. Education can be everywhere, for example the way you get on with someone everyday, how you talk to them, looking at your mother cooking, or observing how mother talks to and treats other people. The situation of Hong Kong is such that many things are turned into systems, and in this way we lose the ability to imagine. This is becoming more and more obvious. During the ‘M+ Rover’ school outreach programme, there were many news reports on secondary school students committing suicides. I think one of the reasons is that life doesn’t offer young people hopes and motivations. Adults have to be blamed, as they are invariably the people who define the standards. Nevertheless, in a civilised world, neither youngsters nor the adults are able to see far enough and to be advanced enough to set the standards of the future. Adults narrow-mindedly adopt certain observations in reality to teach youngsters; they don’t provide more imaginative and critical points of view, such as the essence of the standards, or what the standards are in relation to the living at present. But then the indicators are constantly moving, and sometimes we grow old without realising it. But what does it mean to be old, what does it mean to be young, what does it mean to be avant-garde, what does it mean to be conservative? I realised that one must regenerate oneself all the time in order to preserve a kind of energy. It is very important to keep this energy, because in the process of thinking, this energy will make you seem a little younger.

Law Yuk-mui: We have talked a lot about education in Hong Kong, I wonder what it is like in Japan?

Shitamichi Motoyuki: Although contemporary art is taught in many parts of the world, it is taught differently everywhere. They all talk about contemporary art, and there are many different paths that lead to this destination. I can’t say that I have absorbed much from Japanese art education, but after coming to Hong Kong I’ve noticed the difference in educational environment. My experience is that in Hong Kong’s art education, personal feelings are often taken as a departure point for artmaking, this is something I don’t really understand. I’m not saying it can’t be done this way, it’s just that I personally don’t know how to do it this way.

Yim Sui-fong: In art education in secondary schools, students are usually asked to start from their own experiences. For secondary school students, naturally this involves their personal feelings. Is it not the same in Japan?

Shitamichi Motoyuki: In Japan students are usually trained in drawing. They are asked to observe their environment and try to draw it, and they rarely make art starting from their own personal feelings. I think the foundation in art education is laid down very differently in Hong Kong and Japan. In Hong Kong they depart from the personal, which means certain expressions of feelings, while in Japan the focus is on the environment and the main medium is drawing. After arriving in Hong Kong I realised this focus on feelings is the more mainstream and valued approach. I’ve always found this interesting, that’s why I have made observations. Although I don’t know how much of Hin’s works are focused on feelings, I still find this very interesting.